Kutani-yaki (Kutani porcelain) originated in the Kaga City area in Ishikawa Prefecture, and has a history dating back over 360 years. Featuring vivid colours and innovative patterns, this porcelain with overglaze painting is highly rated as one of Ishikawa’s representative crafts.

‘The King of Overglaze Porcelain’ is the title often given to the traditional Japanese porcelain otherwise known as Kutani-yaki. The name refers to both the craft and the creations themselves. Artisans employ the same potting and glazing methods today as they did hundreds of years ago, and the techniques are specific to Kutani-yaki, making it a hugely respected and protected craft.

The stunning ceramics are recognisable by their vibrancy and level of detail, as well as the slight three dimensional appearance of their decoration, due to the techniques used. Bold depictions of natural scenes and geometric patterns are sometimes so intricate that the fact that they have been hand-crafted almost defies belief. This is the magic of Kutani-yaki: It is an extraordinary art form, refined by craftspeople whose skills are undeniable.

The birth of Ko-Kutani

Nowadays, Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys global acclaim. But it was in the tiny village of Kutani, some 400 years ago, that the legacy began.

At the turn of the Edo period (1603-1868), porcelain clay was discovered in the village of Kutani. MAEDA Toshiharu, a lord of the ruling Daishoji Domain (the ancient name of today’s Kaga City area), introduced ceramic techniques from Arita to the area. He then opened a kiln in Kutani, near what is now Yamanaka Onsen.

The production of Kutani-yaki began in 1655. They are distinguishable by their five colour decorative style (known as ‘go-sai’), using green, yellow, purple, dark blue, and red pigments. But Ko-Kutani porcelain production was short-lived. The kilns in Kutani village suddenly disappeared after some 50 years, the Kutani-yaki that was then produced was later called Ko-Kutani (Old Kutani), which became the roots of the current Kutani-yaki.

Restoration of Kutani-yaki

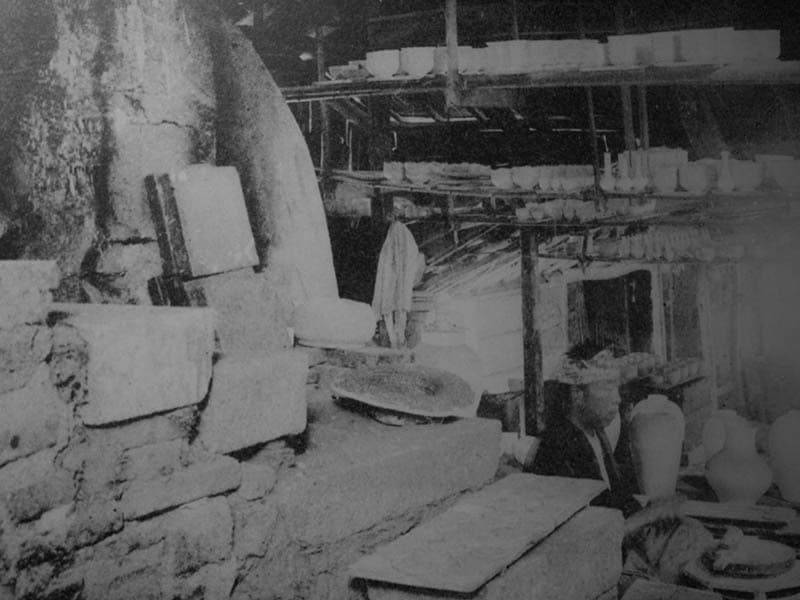

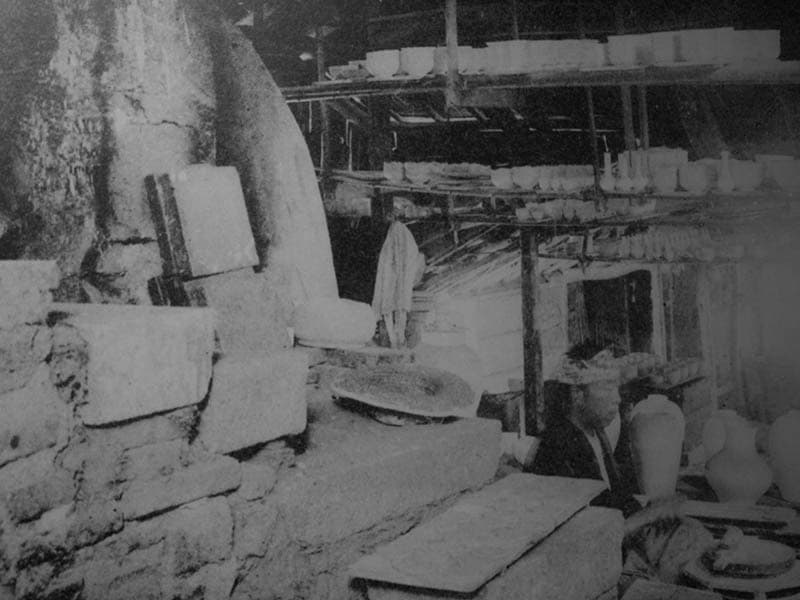

In 1824, a rich merchant from Daishoji Domain, YOSHIDAYA Den’emon, built another kiln in the village of Kutani adjacent to the old site of the Ko-Kutani kilns, and succeeded in reviving the lost porcelain. Then the kiln was moved by YOSHIDAYA two years later in 1826 at Yamashiro Onsen (presently the site of the Kutani-yaki Kiln Museum) and was used until 1940. For several decades works from this Yoshidaya kiln were the only pottery known as Kutani-yaki back then and it was the original source of Kutani porcelain.

At that time, the Kutani-yaki made in his kiln had a good reputation among cultural people for its artistry and quality that was comparable to Ko-Kutani ware. Later, it was taken over by several kiln owners, who then established various forms and painting styles of Kutano-yaki, such as the Ko-Kutani, Yoshidaya, Iidaya, and Eiraku styles.

The Kutani-yaki to the present day

In 19th century, gradually more kilns opened across the regions and Kutani-yaki became hugely popular. The Meiji period (1868-1912) saw a rise in the export of Kutani-yaki as a trade item. At that time, kiln owners across Ishikawa Prefecture branded all of their porcelain with overglaze painting as Kutani-yaki and they exported it. In 1873 a showcase of Kutani-yaki at the World Expo in Vienna introduced the beautiful art form to the West for the first time, leading to the worldwide spread of the name ‘Japan Kutani’. As its reputation in Europe grew, Japanese artisans adopted more Western painting and glazing techniques to appeal to the Western market. As a result, many contemporary Kutani-yaki designs bears resemblance to the tableware of noble European dining rooms.

The current Kutani-yaki works developed a variety of originalities based on the traditional forms and painting styles. They are produced as artwork while designs for everyday use are also created in accordance with a new lifestyle.

Uwaetsuke technique and Kutani-yaki styles

What makes Kutani-yaki so unique is its use of under and over-glazing painting techniques. ‘Uwaetsuke’, as it is known in Japanese, is the art of applying colour and decoration to already-fired porcelain, before once more firing it in the kiln. A chemical reaction occurs in the kiln and the pigments melt, bond, and turn translucent on the clay. Their colours also change, so that the result is an almost luminous piece of porcelain.

Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys a few distinctive decorative styles, notably: aote, iroe and akae. Aote is the most prominent. It omits red and only uses green, yellow, dark blue and purple hues. Aote designs usually cover the majority of the porcelain’s surface. Iroe makes use of all five colours, and usually depicts people and nature. Akae pieces are usually red in colour. Taking advantage of the unique characteristic of overgraze enamel red this style paints detailed fine figures on the entire surface.

The birth of Ko-Kutani

Nowadays, Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys global acclaim. But it was in the tiny village of Kutani, some 400 years ago, that the legacy began.

At the turn of the Edo period (1603-1868), porcelain clay was discovered in the village of Kutani. MAEDA Toshiharu, a lord of the ruling Daishoji Domain (the ancient name of today’s Kaga City area), introduced ceramic techniques from Arita to the area. He then opened a kiln in Kutani, near what is now Yamanaka Onsen.

The production of Kutani-yaki began in 1655. They are distinguishable by their five colour decorative style (known as ‘go-sai’), using green, yellow, purple, dark blue, and red pigments. But Ko-Kutani porcelain production was short-lived. The kilns in Kutani village suddenly disappeared after some 50 years, the Kutani-yaki that was then produced was later called Ko-Kutani (Old Kutani), which became the roots of the current Kutani-yaki.

Restoration of Kutani-yaki

In 1824, a rich merchant from Daishoji Domain, YOSHIDAYA Den’emon, built another kiln in the village of Kutani adjacent to the old site of the Ko-Kutani kilns, and succeeded in reviving the lost porcelain. Then the kiln was moved by YOSHIDAYA two years later in 1826 at Yamashiro Onsen (presently the site of the Kutani-yaki Kiln Museum) and was used until 1940. For several decades works from this Yoshidaya kiln were the only pottery known as Kutani-yaki back then and it was the original source of Kutani porcelain.

At that time, the Kutani-yaki made in his kiln had a good reputation among cultural people for its artistry and quality that was comparable to Ko-Kutani ware. Later, it was taken over by several kiln owners, who then established various forms and painting styles of Kutano-yaki, such as the Ko-Kutani, Yoshidaya, Iidaya, and Eiraku styles.

The Kutani-yaki to the present day

In 19th century, gradually more kilns opened across the regions and Kutani-yaki became hugely popular. The Meiji period (1868-1912) saw a rise in the export of Kutani-yaki as a trade item. At that time, kiln owners across Ishikawa Prefecture branded all of their porcelain with overglaze painting as Kutani-yaki and they exported it. In 1873 a showcase of Kutani-yaki at the World Expo in Vienna introduced the beautiful art form to the West for the first time, leading to the worldwide spread of the name ‘Japan Kutani’. As its reputation in Europe grew, Japanese artisans adopted more Western painting and glazing techniques to appeal to the Western market. As a result, many contemporary Kutani-yaki designs bears resemblance to the tableware of noble European dining rooms.

The current Kutani-yaki works developed a variety of originalities based on the traditional forms and painting styles. They are produced as artwork while designs for everyday use are also created in accordance with a new lifestyle.

Uwaetsuke technique and Kutani-yaki styles

What makes Kutani-yaki so unique is its use of under and over-glazing painting techniques. ‘Uwaetsuke’, as it is known in Japanese, is the art of applying colour and decoration to already-fired porcelain, before once more firing it in the kiln. A chemical reaction occurs in the kiln and the pigments melt, bond, and turn translucent on the clay. Their colours also change, so that the result is an almost luminous piece of porcelain.

Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys a few distinctive decorative styles, notably: aote, iroe and akae. Aote is the most prominent. It omits red and only uses green, yellow, dark blue and purple hues. Aote designs usually cover the majority of the porcelain’s surface. Iroe makes use of all five colours, and usually depicts people and nature. Akae pieces are usually red in colour. Taking advantage of the unique characteristic of overgraze enamel red this style paints detailed fine figures on the entire surface.