‘The King of Overglaze Porcelain’….

…is the title often given to the traditional Japanese porcelain otherwise known as Kutani-yaki. The name refers to both the craft and the creations themselves. Artisans employ the same potting and glazing methods today as they did hundreds of years ago, and the techniques are specific to Kutani-yaki, making it a hugely respected and protected craft.

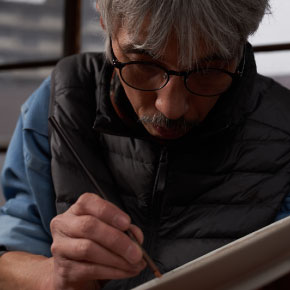

The stunning ceramics are recognisable by their vibrancy and level of detail, as well as the slight three dimensional appearance of their decoration, due to the techniques used. Bold depictions of natural scenes and geometric patterns are sometimes so intricate that the fact that they have been hand-crafted almost defies belief. This is the magic of Kutani-yaki: It is an extraordinary art form, refined by craftspeople whose skills are undeniable.

The Early Years of Ko-kutani

Nowadays, Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys global acclaim. But it was in the tiny village of Kutani, some 400 years ago, that the legacy began.

At the turn of the Edo period (1603-1868), porcelain clay was discovered in the village of Kutani. MAEDA Toshiharu, a lord of the ruling Daishoji Domain (the ancient name of today’s Kaga City area), introduced ceramic techniques from Arita to the area. He then opened a kiln in Kutani, near what is now Yamanaka Onsen.

The production of Kutani-yaki began. The ceramics produced from that time are today known as Ko-Kutani, literally ‘old kutani’. They are distinguishable by their five colour decorative style (known as ‘go-sai’), using green, yellow, purple, dark blue, and red pigments. But Ko-Kutani porcelain production was short-lived. In less than a half century the kiln had closed down, the reasons unknown.

The Style of the Century

An almost century-long hiatus ensued, after which began the revival of Kutani-yaki porcelain and pottery. This new form of Kutani-yaki, produced from the 19th century onwards, is referred to as ‘Saiko-Kutani’ and sometimes uses slightly different colour combinations to Ko-Kutani.

At the turn of the 19th century, Yoshidaya Den’emon, a rich merchant from the Daishoji Domain commissioned a new kiln in Kutani. He was able to bring Kutani-yaki porcelain production back to life.

Gradually, more kilns opened across the region and Kutani-yaki became hugely popular. In 1873 a showcase of Kutani-yaki at the World Expo in Vienna introduced the beautiful art form to the West for the first time. As its reputation in Europe grew, Japanese artisans adopted more Western painting and glazing techniques in order to appeal to the Western market. As a result, many contemporary Kutani-yaki designs bear resemblance to the tableware of noble European dining rooms.

Uwaetsuke

What makes Kutani-yaki so unique is its use of under and over-glazing painting techniques. ‘Uwaetsuke’, as it is known in Japanese, is the art of applying colour and decoration to already-fired porcelain, before once more firing it in the kiln. A chemical reaction occurs in the kiln and the pigments melt, bond, and turn translucent on the clay. Their colours also change, so that the result is an almost luminous piece of porcelain.

Decorative Styles

Kutani-yaki porcelain enjoys a few distinctive decorative styles, notably: aote, iroe and akae. Aote is the most prominent. It omits red and only uses green, yellow, dark blue and purple hues. Aote designs usually cover the majority of the porcelain’s surface. Iroe makes use of all five colours, and usually depicts people and nature. Akae pieces are usually red in colour. Taking advantage of the unique characteristic of overgraze enamel red this style paints detailed fine figures on the entire surface.

Modern Day Kutani-yaki

Today, many contemporary Kutani-yaki styles are in existence, including depictions of anime characters, but Kaga Kutani-yaki keeps with tradition. Its features and styles are a result of small, family-run kilns which take care of the entire process from start to finish. However, while once a porcelain exclusive to the upper classes, today’s Kutani-yaki includes affordable pieces meant for everyday use.

The high-level of skill required to produce these exquisite ceramics is undeniable. At Yamashiro Onsen’s fascinating Kutani-yaki Kiln Museum, visitors can marvel at the intricacy and beauty of creations old and new and try their hand at potting and painting themselves. The museum also houses the impressive ruins of the original kiln used to bake Kutani-yaki porcelain from the end of the Edo era (1603-1868) to 1940.